The word Mycology was first used in 1836 by M.J Berkeley who later donated his entire fungal collection to Kew; because of the importance of such a collection RBG Kew appointed the first mycologist: M.C. Cooke to take care, study and add to the collection. The collection is now the largest in the world and one of the most comprehensive

Before the development of the microscope (e.g. Linnaean taxonomy) fungi were grouped very roughly according to external shape, concepts of how the fungi are related have changed drammatically through the years.

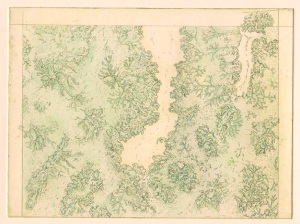

I found an old engraving of the grotto of Antiparnas in the Wellcome Trust Image Library and it reminded me of the forms I had seen before in some fungi-

I decided to re-draw the grotto landscape replacing its landscape forms with mushroom specimens I found in the Mycology Collection.

Kew’s collection is still being organised mostly by morphological concepts, unless new genera are brought in.

Once I had re-drawn the grotto using mushrooms- I made a diagram of the composition, identifying each specimen in the work- Each specimen is drawn directly from life onto the copper etching plate and is true scale-

List of specimens in this work-

1. Daldina concentrica – popularly known as King Alfred’s cakes (http://www.woodlands.co.uk/blog/conservation/king-alfreds-cake/)

2. Sphaeria gunni , the name of this species now is Cordyceps gunnii

3. Amanita muscaria or fly agaric; for this you have a nice little history you can read in the book by Spooner & Roberts (2005) Fungi: pages 468-469. Collins New Naturalist Series (here in the library), on how the Vikings took it to go ‘berserk’

4. Herb hort

5. Fly agaric this is also Amanita muscaria (see above)

6. Schizophyllon commune ; a widely distributed fungus (see http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Schco1/Schco1.home.html)

7. Tuber aestivum 162512 ; on truffles the best thing would be to check Brian’s book, but I cannot find it in the library now; someone must have borrowed it. The reference is: British truffles : a revision of British hypogeous fungi / D. N. Pegler, B. M. Spooner, T. W. K. Young (1993), published by RBG Kew.

8. Daldina concentrica (see above)

9. Armillaria mellea or honey fungus, is also known as the gardener’s curse as it is parasitic in all sort of gardens plants and timber trees (see http://apps.rhs.org.uk/advicesearch/Profile.aspx?pid=180)

10. Stemonitis ferruginea ; is a slime mould or myxomycete, now in the Kingdom Protozoa instead of Fungi; but traditionally these organisms have been studied by mycologists. As you can see in the old plate by Haeckel of 1904 (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slime_mold) they were once included in the Kingdom Animalia as ‘myzetozoa’. They eat bacteria and organic matter from the soil.

Mycologist Begone Aguirre Hudson helped me to research each specimen and the use of drawing in Mycology- Here is a conversation with her-

Gemma- I saw some drawings of specimens from microscopes- can you tell me about how drawing is still used in mycology and why it is important?

Begona- Traditional mycologists like Brian or myself used them all the time. †We could not do without them. †We cheat by using drawing tubes attached to the microscope, but sometimes the drawings are free hand on millimetre paper, to make the measurements and shapes comparable from one fungus to the next ( I do the latter).

Gemma-you described the mycology collection as a kind of archaeological collection?

I meant like an archaeological dig. †In these, you are not allowed to removed everything at once (unless it is going to be destroyed by the construction of a road, or building), but you only excavate a little, so that in the future, with new methods and techniques you can learn more about the place, and the culture of the inhabitants. †The fungal collection, is similar, is a reference collection. †You study the material, but always make sure that you keep the drawing, slides, etc, and leave more material for further studies. †As you can see over the years new techniques bring new approaches to the classification, so we keep the voucher to make sure that we all know (refer to) what we are talking about.

Gemma- Are new species of mushrooms found often? If so are they still drawn – and is there shape studied? †

Begona- Yes,

To publish a new name the Botanical Code of Nomenclature you need: a description in Latin, and various other conditions, but most people nowadays include also pictures, either photos or drawings to accompany the description . †Watercolours is more a thing of the past. †If I am asked to review a paper with a new species, etc, I usually request that the drawings and the pictures are good and informative, not just pretty.